Eric Griffiths cared too much about his students’ potential to let them wallow in sloppy thoughts

Jun 28th 2018| CAMBRIDGE

If Not Critical. By Eric Griffiths. Edited by Freya Johnston. Oxford University Press; 272 pages; $35 and £25.

DRESSED in a leather jacket and a shoelace-thin tie, or with Armani trousers flapping around his trainers, Eric Griffiths would begin as soon as he reached the lectern. He spoke, as Hamlet instructed the actors, “trippingly”, pausing only to take small sips of a drink that looked like water, or one that looked like apple juice. His lectures were packed; they were such a hot ticket at Cambridge in the 1980s that Varsity, the student newspaper, listed them in its entertainment guide. When Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, now a professor of English at Oxford University, first attended, he asked the student next to him, “Are these going to be any good?” “Don’t bother taking notes,” she said, “just enjoy the show.”

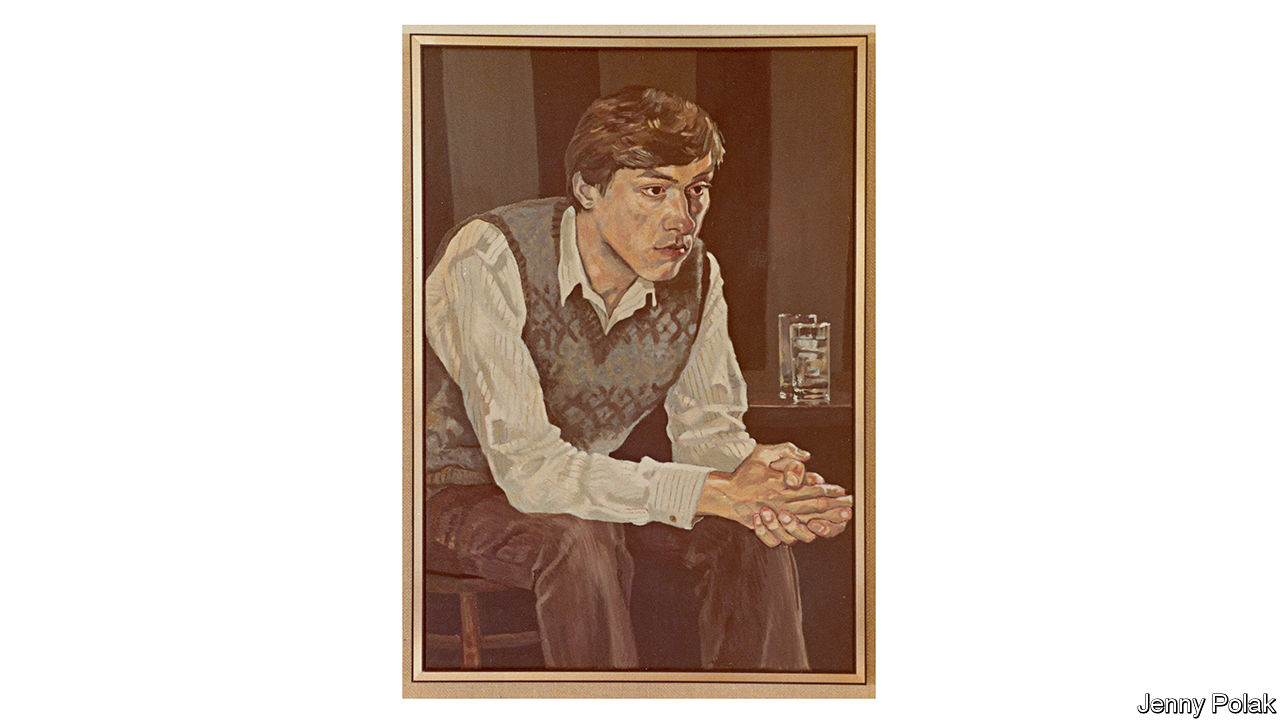

The performance was electrifying. Not just because the audience was uncertain whether, at any moment, Mr Griffiths (pictured) might hurl a book or jump off the stage or produce a drum to beat out the rhythm of a line of poetry. Or because his voice might rise into a pinpoint impression of Dame Edna Everage, or of a character from “EastEnders”, a British soap-opera, speaking cod-Shakespearean pentameters. Because it seemed as if he had something fresh to say about every word in European literature and the spaces between them.

A selection of Mr Griffiths’s lectures has now been published as “If Not Critical”. It would be heretical to say their wit, vitality and acumen leap off the page, because Mr Griffiths does not think words work that way. In the “Printed Voice of Victorian Poetry”, his only full-length book, he argued that written texts are knotted with ambiguity because they lack the cues of speech—tone, gesture, facial expression and so on. The greatest works of literature are thus latent with possible readings.

“If Not Critical” covers writers he prizes such as Shakespeare, Dante and Racine. The word “Divina” of the “Divina Comedia”, Mr Griffiths says, is a publisher’s puff that “means something like ‘fabulous poem, darling, loved it loved it loved it’.” He is one of the most skilful practitioners of close reading, an approach to criticism indigenous to Cambridge. His attention to detail is never pedantic, but provides clues to attitudes and beliefs. For example, the epithet “Kafkaesque” is often lazily applied to any situation with a tingle of bureaucratic menace; Mr Griffiths shows how the mood is produced by small words such as “if” and “but”, around which Kafka’s sentences twist and pivot.

Mr Griffiths attracts superlatives. The Guardian once declared him the “cleverest man in England”. Donald Davie, a poet and critic, called him the “rudest man in the kingdom”. And for many of the pupils he taught over 30 years at Trinity College, Cambridge, he was the greatest teacher they ever had. From today’s perspective, his approach was, to say the least, unorthodox. He would tease and mock, provoke and scorn. Colin Burrow, who was taught by Mr Griffiths before becoming a colleague, recalls that “he had the enormous art of pouncing on what looked like a minor infelicity of phrasing and then teasing out from that the gross conceptual error that lay beneath it. One would sit there…feeling a bit like a terrified mouse confronted by a devastating feline opponent.”

But his ferocity was a sign that he cared. He cherished his students’ potential too much to let them wallow in sloppy thoughts. He examined their work with as much scrutiny as he devoted to T.S. Eliot and Wordsworth. Simon Russell Beale, an actor, remembers that he would write his essays on one side of the paper and Mr Griffiths would respond with an essay of his own on the back. A tick in the margin was gold-dust. “I left every lecture and every class thinking that I had learned more about trying to be a better human being,” says another acolyte.

He was one of the last generation of fellows to live in college, and his life was entwined with his students’ lives beyond the confines of lessons. He held parties (“Come and be louche”, read the invitations), where poetry was read, and Wagner and the Pet Shop Boys were played at full blast. He flirted. A trip to Tennyson country in Lincolnshire ended with whiskey being swilled in a ditch. Not everyone enjoyed the tutelage of a charismatic teacher who was part exacting literary conscience, part Pied Piper. Especially after a drink, Mr Griffiths’s tongue could be harsh. He once dismissed a female student’s contribution as “mildly decorative”.

Such asperity came back to bite him. He thrived as a media don in the 1980s, when TV schedulers enjoyed the sight of highbrows feasting on pop culture; he filmed a documentary about Talking Heads, one of his favourite bands. But his career was derailed after he sniped on-air that A.S. Byatt’s Booker-winning novel, “Possession”, was “the kind of novel I’d write if I was foolish enough not to know I couldn’t write a novel”. In 1998 he was embroiled in a scandal after a state-school applicant claimed that, during her interview, Mr Griffiths pointed to some words in Greek and said, “being from Essex you wouldn’t know what these funny squiggles are.”

Alas and alack

He disputed that account, but the college stopped him interviewing. The press portrayed him as a snob, though he was the son of a Liverpool docker and himself state-educated. As it turned out, 1998 was a watershed for British education more widely. The Labour government introduced tuition fees, which made the relationship between students and universities more transactional. Mr Griffiths’s bracing style was not in keeping with the era of student-satisfaction surveys. He carried on teaching, but was calmer and more self-contained. His belief that you could mould the mind of an 18-year-old dwindled. A blackboard in his rooms bore the words, “How the fuck should I know?”

In 2011, after being hospitalised for a heart-attack, Mr Griffiths suffered a stroke. He was 57; he has since spoken only in stutters. It was as if he had been struck down with the vengeful precision of Greek myth: if a special circle of hell were constructed for him, he once said, it would involve having his tongue cut out. But the voice—precise, interrogatory and sarcastic, and also, in private, generous and encouraging—can still be heard. “I can only read ‘If Not Critical’ in small bits”, says his friend, the poet Alice Goodman, “because it’s his voice.” From his hospital bed, he told a friend that “if that was the last lecture I give, I’m glad it was on the important semantic differences between ‘alas’ and ‘alack’.”This article appeared in the Books and arts section of the print edition under the headline “The art of pouncing”

Source: The Economist